Tangible versus Intangible Assets

지난 20년 동안 기업은 장부가치보다 시장가치가 훨씬 앞섰다. 그만큼 무형자산의 가치가 높다는 의미이다.

우리는 무형자산의 가치연구에 많은 시간을 할애하여야 하겠다. 무형자산이야 말로 미래의 자산이며 가치

창출의 엔진이기도 하기 때문이다.

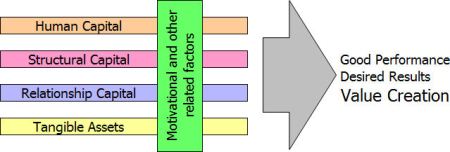

I described in an earlier post (see: “KM is Not Enough!”) the factors that contribute to good

performance or value creation:

We must note the following to better grasp the intricacies of tangible and intangible assets:

- In the last two decades, market values of most corporations now far exceed their book values

(for example, as of December 12, 2008 the market-to-book ratios of 215 industry groups

listed in Yahoo! Finance averaged 4.458). This means that intangible assets are contributing

more than tangible assets in creating value. - There are many evidences across various sectors and disciplines that intangible assets are

more important than tangible assets in creating value (see previous post on “Intangibles: More

Essential for Value Creation”). - International accounting standards recognize “intangible assets” as such if they are: non-

physical, owned by the corporation, and can generate future economic benefits. Because of

the ownership criterion, many corporations do not consider the human capital they hired and

the intangibles that their personnel create (e.g. internally developed software and other

structural capital) as assets to be entered in their books of account, although these definitely

contribute to value creation by the corporation. In fact, training is often considered as a cost

item, instead of a capital investment item. The intangible assets commonly recognized by

accountants are: goodwill, brand, intellectual property rights like patents and copyrights,

licenses/franchises and similar legal agreements, etc.

- The intellectual capital accounting school of KM (e.g. Karl Erik Sveiby, Leif Edvinsson, Thomas

Stewart, Patrick Sullivan, Baruch Lev, etc.) recognizes three categories of intellectual capital:

human capital, structural capital and stakeholder capital (which includes customer capital

proposed by Hubert Saint Onge) – which contribute to value creation but are missed by

traditional accounting methods. These three categories are also recognized as “knowledge

assets”. Note, however, that stakeholder capital is only the externally-facing part of

Relationship Capital in the model diagrammed above (see next blogpost “D12- Relationship

Capital versus Stakeholder Capital versus Consumer Capital”). Elements of intellectual capital

are often not entered in books of accounts – a management gap which paved the way for

various methods of “intellectual capital accounting”, Kaplan and Norton’s Balanced Scorecard,

US Securities and Exchange Commission’s “colorized reports”, etc.

- Knowledge assets are mainly intangible and often not entered in books of accounts. A common

example of tangible knowledge assets is technology, which is a form of “embedded

knowledge”. Examples of knowledge assets not always entered in book of accounts are trade

secrets and internally developed patents (those that were not bought or sold by the

organization). - To encompass the wide range of factors (including natural capital, social capital, indigenous

knowledge, traditional or government-sanctioned access rights, cultural capital, etc.) that

contribute to value creation, whether tangible or intangible, whether measured or not by

accountants, we proposed the term “metacapital” (see the bottom of the previous post on

“Valuation of intangible assets”).

'이원모칼럼(Lee' Opinion)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [The New York Times] 현명한 사람의 6가지 정신적 특징 (0) | 2014.09.03 |

|---|---|

| 성공의 지름길 (0) | 2014.06.05 |

| 실로 오랫만에 기대한 사람 (0) | 2014.05.22 |

| 八정도(正道)-바르게 가는 길 (0) | 2014.05.15 |

| 의사결정 五常의 행복 (0) | 2014.05.14 |